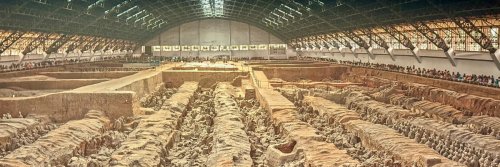

Currently on display at the WA Museum Boola Bardip in Perth until Sunday, 22nd February 2026, the legendary Terracotta Warriors will take your breath away. Created during the reign of Qin Shi Huang (who was consumed with his end-of-life planning and an obsessive quest for his own immortality), the warriors have been on display at more than 270 major exhibitions outside of China in more than 50 countries, including Finland, Italy, the United Kingdom, Japan, and the United States. Which is a bonus if you don't fancy searching for cheap airfares, grabbing your passport, indulging in crappy airport fare before flying off to Xi’an, China, with the tourist hordes.

This astounding exhibition features over 225 artefacts, including eight original terracotta figures that dominate their surroundings of handcrafted clay soldiers (large doll size), lifelike and life-size horses and chariots, various small clay animals, and showcasing fierce-looking protective armour—everything one would expect to need in the afterlife of an emperor. It's a brush with ancient history that will have you wetting your pants in excitement as one can imagine them grandly guarding the underground lair, or should I say, ‘funeral compound’ that took more than 700,000 industrious minions, many of whom died, 39 years to build.

The exhibition smoulders in low lighting, invoking a sense of entering a forbidden tomb. From the small, doll-sized soldiers to the overbearing stance of the larger-than-life warriors, each soldier has distinctly different features: cutesy warriors' buns perched on their heads to the somewhat cynical and sometimes quirky smiles on their faces—no two are alike. Some even have the faintest traces of their original paint, a colorful reminder that these earthen guardians were once far from monochrome. They were initially smothered in colorful pigmentations created from minerals such as azurite, malachite, and cinnabar. It was exposure to light and air that caused the coloring to fade. There’s a palpable sense of awe among visitors, who shuffle from archer to general, whispering in reverent tones as if the warriors might suddenly spring to life and demand to know where you’ve hidden your dumplings.

What struck me most was the meticulous detail—each warrior is unique, a testament to the ancient artisans’ dedication (and possibly, a touch of workplace rivalry). The exhibition doesn’t just dump you in front of statues either; it thoughtfully guides you through the history and the mystery. It's a crash course in ancient Chinese culture, with interactive displays and enough engaging information to keep you reading as you wander through the exhibition. I was blown away by the fact that it takes two years to carefully restore just one warrior to its former glory. And, just when you believe you are walking out of the exit door, you are assailed by the brightly colored and romanticized version of what the emperor may have been expecting his eternal life to look like in a wall-to-wall and pseudo-liquid floor display of his nirvana.

The tomb of Qin Shi Huang, China's first emperor, was accidentally discovered in 1974 by local farmers in a village near Mount Li, outside the major city of Xi'an, while they were digging a well. They struck pottery fragments, which led to the unearthing of one of the life-size warriors. Further excavation revealed the mammoth army positioned in battle formation under the weight of the ancient earth. In light of this, Chinese archaeologists dug further into the ground to discover the mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang, one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of the 20th Century. It consisted of numerous tombs and burial pits, along with multiple traps to ward off tomb raiders, including hidden shooting crossbows, death traps, and a large amount of mercury. The liquid mercury is believed to have been used as a symbolic representation of the geography, rivers, and oceans of his empire that would aid him in his afterlife.

Often portrayed as a tyrant, Qin Shi Huang founded the Qin Dynasty (221-210 BCE), China’s first feudal dynasty. He was the first to assume the title ‘emperor’ (which title remained in use for the next 2,000 years) instead of ‘king’, and is credited with unifying the Chinese empire. He standardized the Chinese writing system, weights, measures, and coinage. His other achievements include linking the Great Wall of China to protect the northern border and building the Ling Canal, which connected the south and north river systems. On the flip side, he had a penchant for burying Confucian scholars, and it's said that human sacrifices were replaced by his reportedly 8,000 terracotta warriors. Another glitch in his personality, for me, is the fact that he buried his concubines in his tomb while they were alive so that they could serve him in his afterlife.

Qin Shi Huang died at the age of 49 in 210 BCE, with some believing it was due to his court alchemists and physicians giving him elixirs laced with mercury to aid in his quest for immortality, which is quite ironic. To date, his imperial chamber remains a mystery, as it has never been excavated and opened, because scientists are waiting for the necessary advancements in technology to prevent any damage that the air and light may cause.

Gail Palethorpe, a self proclaimed Australian gypsy, is a freelance writer, photographer and eternal traveller. Check out her website Gail Palethorpe Photography and her Shutterstock profile.